The Witches in Macbeth, also known as the ‘weird sisters’, are three mysterious figures who make a series of prophecies, including that the Scottish warrior Macbeth will become King and that his friend Banquo will father a line of kings. Macbeth, who begins the play as Thane of Glamis and then, as prophesised by the Witches, becomes Thane of Cawdor, conspires with his wife to make sure these prophecies become true. The Witches are supernatural beings, meaning that they appeal to forces beyond the laws of nature: they vanish after their encounter with Macbeth and Banquo on the heath in Act 1 Scene 3. Banquo says that ‘The earth hath bubbles, as the water has, / And these are of them’ (1.3.77-8), and Macbeth acknowledges that they have vanished ‘Into the air, and what seemed corporal / Melted as breath into the wind’ (1.3.79-80). Banquo wonders if the Witches are ’fantastical or that indeed / Which outwardly ye show’ (1.3.51-2) and whether he and Macbeth have ‘eaten on the insane root / That takes the reason prisoner’ (1.3.82-3), his heightened language stressing their otherworldly nature. In presenting these supernatural beings, Shakespeare explores a tension between the ideas of fate and free will. The Witches appear to have knowledge of future events, but it is Macbeth and his wife’s ambition that ensures the Witches’ prophecies become reality when the Macbeths commit the worst of political crimes, regicide, and murder King Duncan.

Macbeth was written around 1606. Three years earlier, King James VI of Scotland also became King of England. Not only did he become King; he became Shakespeare’s theatre company’s patron. Shakespeare’s company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, were therefore renamed the King’s Men and became the dominant acting company in Jacobean London. However, having King James I as his company patron meant that Shakespeare had to tread especially carefully to not offend the monarch. If you offended the monarch during this period, you ran the risk of having your nose or ears slit, or even being publicly executed. Shakespeare takes a cautious approach to his source material, the 1587 edition of Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland. In Holinshed’s account, Macbeth and Banquo plot King Duncan’s death together. King James saw himself as a direct descendant of Banquo’s, so Shakespeare departs from his chronicle source material with Banquo playing no part in the conspiracy. King James also had a fixation on the supernatural, which Shakespeare mirrors in Macbeth. Playmaking was an entertainment industry, and Shakespeare needed to ensure that the themes and topics he explored in his plays were topical and relevant for audiences. James wrote a work about the supernatural, titled Daemonologie and published in 1597. The King was an advocate of witch hunting. In 1589, while sailing from Denmark to Scotland, he experienced a dreadful storm, which he attributed to witchcraft. In the following year, many people in East Lothian, Scotland, were accused of witchcraft during the Berwick Witch Trials and in 1603 the Witchcraft Act made it a capital offense to communicate with spirits.

Macbeth was first performed during a particularly superstitious period, when people believed in witchcraft, magic and demons. Magic could be good or bad: it was believed that 'cunning folk' helped cure diseases and countered dark magic in communities. Many households in Shakespeare’s England kept a vessel known as a ‘Bartmann jug’, or ‘bearded man jug’, which could be used to trap evil spirits. These vessels might be filled with hot urine, nail clippings, even little pieces of fabric cut into the shape of hearts. In Macbeth, the Witches communicate with ‘familiars’, animal spirits such as a cat named Graymalkin, a toad called Paddock and a creature named Harpier, reflecting the belief in Jacobean society that witches were often accompanied by demonic assistants.

We can imagine Shakespeare’s audiences at the Globe playhouse, where his company performed from 1599 onwards, seeing Macbeth for the first time. This open-air playhouse had a capacity of around 3000 people from all sorts of backgrounds, including tailors, leather workers, trainee lawyers, butchers, foreign ambassadors and thieves. For a penny, the price of a loaf of bread at the time (or attendance at a public execution), audience members at the Globe could join the ‘groundlings’ or ‘stinkards’, a term that conjures the mixture of smells in the playhouses of the day. The ‘groundlings’ standing in the pit would be close to the ‘thrust’ stage when performances began at approximately two o’clock in the afternoon. For two pennies, audience members could sit in the gallery, and for three pennies they could enjoy a cushion. Wealthier citizens might pay a shilling (around twelve pennies) for a seat in the box, where it was more about being seen by other audience members than necessarily having the best seats for seeing the play itself. Shakespeare and his company would be aware that there would be a lot of commotion in the pit at the Globe playhouse before a play began, including fights breaking out and thieves picking pockets. Shakespeare grabs audience attention through a stimulating opening that makes great use of the properties of the Globe stage and instantly reveals the Witches’ supernatural origins. The ‘weird sisters’ might emerge through the trap door, and a creepy storm could have been simulated through fireworks, beating drums, thunder sheets or rolling a cannonball along the rafters.

Shakespeare also reveals the Witches’ otherworldly nature through the ways they speak: not in traditional iambic pentameter, with unstressed syllables followed by stressed and usually ten syllables per verse line. Instead, he uses trochaic tetrameter, a very different rhythm with seven to eight syllables per line, stressed syllables followed by unstressed: ‘When shall we three meet again? / In thunder, lightning, or in rain?’ (1.1.1-2). Our sense of the Witches as supernatural beings is also aided through the ways in which they are described. Banquo says that they have ‘choppy’ fingers and ‘skinny lips’ (1.3.41-2). He also says that ‘You should be women, / And yet your beards forbid me to interpret / That you are so’ (1.3.43-5). Shakespeare places considerable emphasis on language because he needs his audiences to listen attentively to his dramatic dialogue to convey setting, mood and characters.

The Witches also afford numerous opportunities for striking stage effects. The ‘weird sisters’ have exchanges with Hecate: the goddess of magic, the night, the moon and necromancy (or communication with the dead). Macbeth alludes to her when he describes a supernatural dagger:

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?

I see thee yet, in form as palpable

As this which now I draw.

Thou marshall'st me the way that I was going,

And such an instrument I was to use.

Mine eyes are made the fools o' th’ other senses,

Or else worth all the rest. I see thee still,

And on thy blade and dudgeon gouts of blood,

Which was not so before. There's no such thing.

It is the bloody business which informs

Thus to mine eyes. Now o'er the one half-world

Nature seems dead, and wicked dreams abuse

The curtained sleep. Witchcraft celebrates

Pale Hecate's offerings, and withered murder,

Alarumed by his sentinel, the wolf,

Whose howl's his watch, thus with his stealthy pace.

(2.1.33-54)

Writing for a largely bare stage, Shakespeare uses language to appeal to audience imaginations, to conjure the dagger described by Macbeth. Is there a supernatural dagger or is this a figment of Macbeth’s brain? Shakespeare raises questions, but very rarely provides firm answers, which makes his plays great for study as students can approach these questions with their own personal, informed responses. Shakespeare also aids the actor playing Macbeth, embedding a cue for him to draw his own dagger in this soliloquy, with Macbeth standing alone on stage and offering us insights into his thought processes.

In Act 3 Scene 5, the Witches meet with Hecate on a heath and she scolds them for meddling in Macbeth’s business without first consulting her. This moment, as in Act 1 Scene 1, features a cue for thunder and lightning and even aerial choreography, as Hecate and a spirit exit by riding into the heavens. There is also a cue in this scene for a song beginning ‘Come away, come away’:

HECATE

He shall spurn fate, scorn death, and bear

His hopes ’bove wisdom, grace and fear;

And you all know, security

Is mortals’ chiefest enemy.

SPIRITS (singing dispersedly within)

Come away, come away.

Hecate, Hecate, come away.

HECATE

Hark, I am called! My little spirit, see,

Sits in a foggy cloud and stays for me.

(3.5.30-7)

Another cue for a song beginning ‘Black spirits’ can be found in Act 4 Scene 1 of Macbeth. In this scene Hecate appears and compliments the Witches on their work before Macbeth enters and is shown a series of apparitions. These elements all serve to emphasise the supernatural nature of the Witches, while providing a multimedia spectacle for audiences.

The apparitions in Act 4 Scene 1 rise from a cauldron and include an armed head warning Macbeth to beware of Macduff; a bloody child telling him to ‘Laugh to scorn / The power of man, for none of woman born / Shall harm Macbeth’ (4.1.95-7); and another child, wearing a crown, who tells him that ‘Macbeth shall never vanquished be until / Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinane Hill / Shall come against him’ (4.1.108-10). Macbeth is reassured by these apparitions and comes to believe that he bears ‘a charmed life’ (5.10.12). However, the Witches specialise in equivocation, ambiguous language used to conceal the truth. When enemy soldiers hide their numbers through bearing the branches of Birnam Wood, and when Macduff tells him he ‘was from his mother's womb / Untimely ripped’ (5.10.15-16), Macbeth realises the truth. He calls the Witches ‘juggling fiends no more’ to be ‘believed, / That palter with us in a double sense, / That keep the word of promise to our ear / And break it to our hope’ (5.10.19-22). Earlier in the play Banquo had warned his friend that ‘oftentimes the instruments of darkness tell us truths, / Win us with honest trifles to betray’s / In deepest consequence’ (1.3.121-4). But Macbeth has been seduced by the Witches’ promises, and all too late starts ‘To doubt th’equivocation of the fiend, / That lies like truth’ (5.5.41-2).

The theme of equivocation is also explored through the Porter earlier in the play in Act 2 Scene 3. The Porter is sometimes seen as a supernatural figure who speaks of a ‘porter of hell-gate’ (2.3.1-2) and describes himself as a ‘devil-porter’ (2.3.16). Before admitting Macduff and Lennox into Macbeth’s castle, he speaks of a ‘farmer that hanged himself on th’expectation of plenty’ (2.3.4-5); ‘an equivocator that could swear in both the scales against either scale, who committed treason enough for God’s sake, yet could not equivocate to heaven’ (2.3.8-11); and an ‘English tailor come hither’ (2.3.13). The Porter appears to reference Henry Garnet, a Catholic conspirator involved in the Gunpowder Plot of November 1605. Garnet used the alias ‘Farmer’ and was said to have equivocated during interrogation to avoid lying while still misleading his interrogators. Again, we can see Shakespeare’s play as topical for his Jacobean audiences. The attempt on King James’s life at the Houses of Parliament in the Gunpowder Plot is mirrored by the play, as Macduff enters the castle and discovers that King Duncan has been murdered. The Porter’s darkly comic speeches also serve a practical purpose, as the actors playing the Macbeths, having just murdered King Duncan, are given time to wash away stage blood and change costume in the ‘tiring’ area, backstage.

Shakespeare explores the theme of the supernatural in Macbeth not only through the Witches and the Porter, but also the ghost of Banquo. Ghosts offered Shakespeare opportunities to comment on theatrical illusion, to mirror religious debates of the period and to reflect characters’ guilty consciences. They also offered exciting staging opportunities, as in Macbeth. Stage ghosts were and still are entertaining, although, in theory, Shakespeare’s Protestant audiences shouldn’t have believed in them. Ghosts are purgatorial beings, and purgatory was explicitly denied by the Church of England from 1563 onwards. Writers during the period, such as Reginald Scot in his 1584 book The Discoverie of Witchcraft, argued that apparitions were illusory and sometimes even fraudulent, while other writers believed that some apparitions had bad intentions designed to lead Christians astray. In staging ghosts, writers of the early modern period like Shakespeare were chiefly influenced by Roman tragedies, such as those of Lucius Annaeus Seneca, who staged spectres in his tragedies Thyestes, Agammemnon and Troades. In Shakespeare’s day these ghosts might be represented by an actor wearing flour to enhance their pale appearance, and even blood, represented by dyed vinegar, vermilion paint or drawn from animals.

In Act 3 Scene 5 the Macbeths host a banquet. Macbeth is offered a seat next to the nobleman Ross, but he says that ‘The table’s full’ (3.4.45). He then sees a sight that ‘might appal the devil’ (3.4.59), the ghost of Banquo, whose assassination he ordered. Macbeth responds with a combination of terror and fury as Banquo’s ghost shakes its ‘gory locks’ (3.4.50) at him:

What man dare, I dare.

Approach thou like the rugged Russian bear,

The armed rhinoceros, or th’Hyrcan tiger;

Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

Shall never tremble. Or be alive again,

And dare me to the desert with thy sword.

If trembling I inhabit then, protest me

The baby of a girl. Hence, horrible shadow,

Unreal mock’ry, hence!

(3.4.98-106)

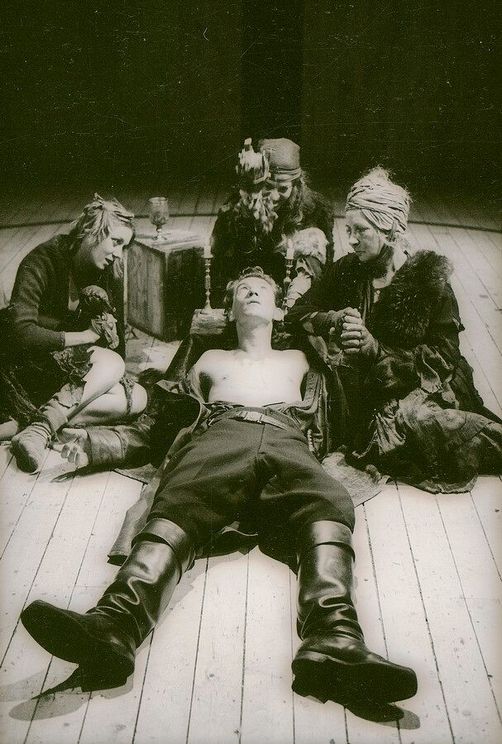

Lady Macbeth dismisses her husband’s reaction: ‘This is the very painting of your fear’ (3.4.60). Banquo’s ghost could be seen as the product of Macbeth’s guilty conscience. Is the ghost real or imaginary? It’s another question Shakespeare raises for his audiences but also for students today. There is a long history of creatives presenting Banquo’s ghost in surprising ways. In the eighteenth century, theatre manager John Philip Kemble refused to stage the ghost, instead inviting his audiences to use their imaginations. Kemble banished the ghost in his productions from 1794 but staged him in 1803 due to popular audience demand! Some productions have offered audiences a combination of approaches: in Michael Boyd’s 2011 Royal Shakespeare Company production, Banquo’s ghost entered and attacked Jonathan Slinger’s Macbeth. After the interval, the scene was replayed without the ghost present, so the audience could relive this moment through the eyes of Macbeth’s terror-stricken guests. Boyd made the decision to increase the ghostliness of the play by having the Witches’ prophecies delivered by what turned out to be the ghosts of Macduff’s murdered children.

Shakespeare presents witches and witchcraft, the supernatural, magic, ghosts and associated themes in Macbeth to serve a variety of purposes. These characters and themes were topical for his audiences, particularly during the reign of King James. Some cultures and individuals still believed in witchcraft, magic and the supernatural. Shakespeare explores debates of the period and offers commentary on theatrical illusion, raising questions about what is real, false or knowable within the tragic world presented in the play. As a practical man of the theatre, he also employs the supernatural to entertain audiences, taking advantage of special effects in much the same way creatives might today. Ghosts, witches and magic were popular during the Jacobean period and remain so, as can be seen in modern literature and movie franchises. Although Macbeth was written over 400 years ago, it still has the power to engage, sometimes even terrify, audiences, and its commentary on themes such as ambition, guilt, power and the abuse of power, fate and free will, can spur fascinating discussions and debates in the classroom.

In partnership with the Foyle Foundation

In partnership with the Foyle Foundation